The questions that I explored this year have been a part of conversations that I have had with teachers over the past few years. When discussing topics with Elena I explored several different possibilities, but when I mentioned that I had been thinking about changing brain development, the role of technology, and the resulting impact on teaching and learning, she strongly encouraged me to look into this further. I have been curious about whether other learning specialists have also observed changes, and if so, if they have made adjustments to their teaching, and how they have adapted their methods and materials.

What triggered this line of thought?

As a learning specialist, it is my job to figure out how a child learns best and to facilitate learning. I am used to the challenge of finding ways to help a child learn when learning is difficult. Yet over the past few years, I have found that my early readers– my first graders who are just learning to crack the code– need more time to learn the same amount of information that I would normally teach during the course of the year. It is taking longer for my students to learn foundation skills, and they are mastering fewer skills in the available time. As a result, students have been moving on less prepared than they have been in prior years, and this has extended the teaching of reading skills for some, from first, far into second grade. For the most part, my second grade students are able to read with some independence, but the amount of material they are able to cover by the end of second grade is also less. The ripple effect of this affects students work in the classroom and the level of independence that they have when they move on to 3rd and 4th grade where greater independence is an expectation. While this has been more pronounced for the students who work with me in particular, I am aware from conversations with classroom teachers, that they have similar concerns and have also seen shifts in learning that have had an impact on what they teach, how much they can teach and how they teach to their students.

As I began to think about all of this, a variety of questions came to mind:

- Are brains changing as a result of technology, and if so, what does it mean to have an old brain and to be teaching to “new” brains that may be developing strengths in different areas than before? Has this happened during other historical periods of significant growth and change?

- Are other learning specialists seeing a similar shift and how have they begun to address it?

- Should I be thinking about new ways of teaching or should I be thinking about timing? Should my teaching timetable shift? Should we all be shifting our timetables?

- Using an Orton Gillingham approach is considered standard practice for children who face challenges with learning how to read. I have always supplemented an Orton program with a variety of other materials and methods but how do I now find a balance that will best support children’s changing learning needs?

- What are people learning from current brain research that can be helpful to me and inform my teaching?

- What do I need to understand about the differences in how I learned/continue to learn, and how children learn today? Aside from possible changes in brain development, how information is received has changed. What do I need to understand about that?

The topic was so broad and deep that at first I found it hard to zero in on how to approach it in a way that could have a direct impact on my teaching. The cohort encouraged me to focus on specifics–a specific child or group or set of skills. While it was my intent to follow that path, to zero in, I found that rather than defining my own path of study through the year, that the topic directed me itself in a variety of sometimes unexpected directions. As a result, I developed new questions from existing questions and ended the year feeling enriched from the experience but without (yet) a completely clear sense of how this can translate into what I do in my room day to day. I have made changes in my daily practice, and am both thinking about things in new ways and thinking about new things, but I am still working on the bigger question of what this all means and how to harness what I have learned, most effectively.

To start the journey, I met with my City and Country counterpart Nancy Vacillaro, to talk about her recent experiences as a Lower School Learning Specialist at a progressive, downtown school. In order to help identify children’s needs earlier, she has brought a 4’s screening to C&C. This is in the form of a checklist that is administered by the classroom teachers and helps them focus on areas that may need more support and development throughout the year. Though an effort on my part to organize a meeting with our Early Childhood teachers before the end of the year, did not work out, I will pick up the thread of this conversation in the fall so that we can look at how much information we already collect, what we do with that information and if there is useful information that we are not looking at in a purposeful way. Understanding the needs of our students as early as possible, will only strengthen our ability to provide an environment that supports their learning.

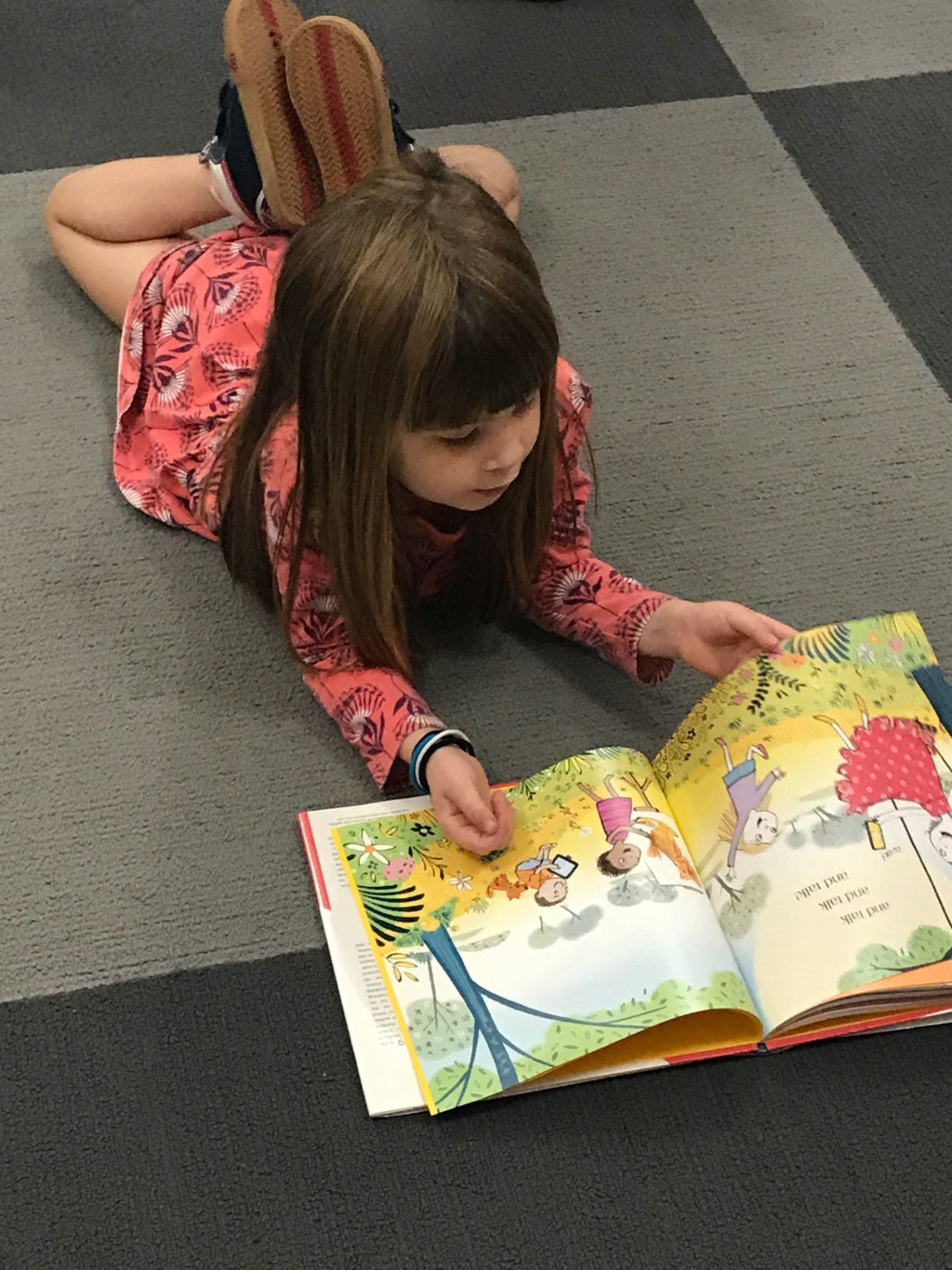

As we moved into fall I found that I had a group of first graders who were not yet ready to start the systematic process of reading instruction. My first question had to be as basic as “ what do I do?” And then, “Why are they not ready?”. The intersection of this particular group and my self study gave me the opportunity to think about all the questions that I was formulating while scrambling to give the children a useful and appropriate reading experience. There was often no time to zero in or to be thoughtful, each day my well planned lessons were scrapped as I tried to figure out what would work. In the past I may have pushed on with the plan, but because of the self study, I decided to follow the lead of the group and to worry less about what they may not be getting in that particular moment. I worked to create experiences that could provide them with moments of learning and success even if they were not the moments I had originally intended or that moved my group as far along the path of learning to read as I hoped. Often I felt frustrated and unsuccessful, but by the end of the year we found our rhythm and the experience provided me with a rich context within which to think about some of the things that I was learning. I relied more heavily on a wider variety of approaches and materials, and began to frame my expectations for growth differently.

Two amazing educational opportunities.

I nearly missed a truly wonderful opportunity to stretch my thinking, engage with other professionals around topics of learning and the brain, and take a few days to regroup and reflect in a beautiful setting. It is hard to disengage, particularly when a group is challenging and it always feels as though there is not enough time to get through what needs to be taught. I somewhat reluctantly found myself at the NYSAIS brain conference in March after Mark and Elena encouraged me to walk away from the classroom for a few days. The conference was a wonderful opportunity to connect with other New York independent school teachers to puzzle over questions about learning. The information presented was interesting, but most interesting for me, were the conversations that came out of the sessions and spilled over into our time outside the formal presentations. I discussed information overload with someone I happened to sit next to, and that led to a fascinating conversation about our own capacity for taking in information during the conference. We agreed that identifying one salient piece of new information to take away, would be our goal. I came away with a new way of thinking about working memory, which is at the core of everything I do as a teacher of early readers. Had I been thinking and talking about it incorrectly? Was I teaching my lessons based on a faulty way of thinking about how information would be stored and retrieved? The new information made sense to me, but so did what I already knew about learning and memory. Conversations with colleagues confirmed that I was not alone in trying to figure out how to think about this new information.

Serendipity

In May, I attended the large, annual, New York Learning and the Brain conference. The conference was three days of workshops and lectures by people from all over the country who would be talking about a wide range of topics related to how the brain learns. Though not the umbrella theme of this years conference, technology and its effect on learning, seemed to feature prominently in almost every session.

On the second day of the conference rain kept many of us inside during the lunch break. Another attendee and I found what we thought was an empty room, but discovered Andrew Watson, the presenter from the NYSAIS conference, working at one of the tables. He recognized me and asked my impressions of the earlier conference. It gave me the opportunity to ask the questions that I had come away with, and to explore the differences between the information that he presented and my previous way of thinking. We talked about how his presentation had challenged the way that I think about memory. He explained that the information could inform and enhance my earlier ways of thinking about working memory, rather than replace them, and we talked about how the two ways of thinking could be merged. That small, unexpected encounter, turned out to be a key moment in my year of exploration.

Conference number one was compact and intense and reinvigorating. Conference number two was broad and deep, presenting a hugely diverse array of learning opportunities. I would not have enjoyed them less, or learned less in another year, but the fact that I attended them during my self study year and had the opportunity to attend both conferences within a couple of months of one another, focused my thinking in a different way. Everything that I heard I thought about within the framework of my self study questions. I continue to think about how that information can move my classroom practice to a new and maybe unexpected place. The final piece of my study was to compile a list of books to read as I move forward. Some I hope to read in their entirety, others have already become reference books that I consult, and still others are books that I will be able to recommend to teachers as I continue my conversations with them about their own experiences with changing student needs.

New ways of thinking and making change.

Working memory is often explained as the brain’s filing system. We tuck learned information away but it has to be easily accessible when we need it. Children with learning difficulties have a hard time getting at the information quickly and efficiently. In the model presented by Andrew Watson, working memory is discussed in terms of capacity, not organization. He stressed that we each have a different capacity for taking in information and that when we hit our limit, we are unable to take in more until we rest, step away and reset.

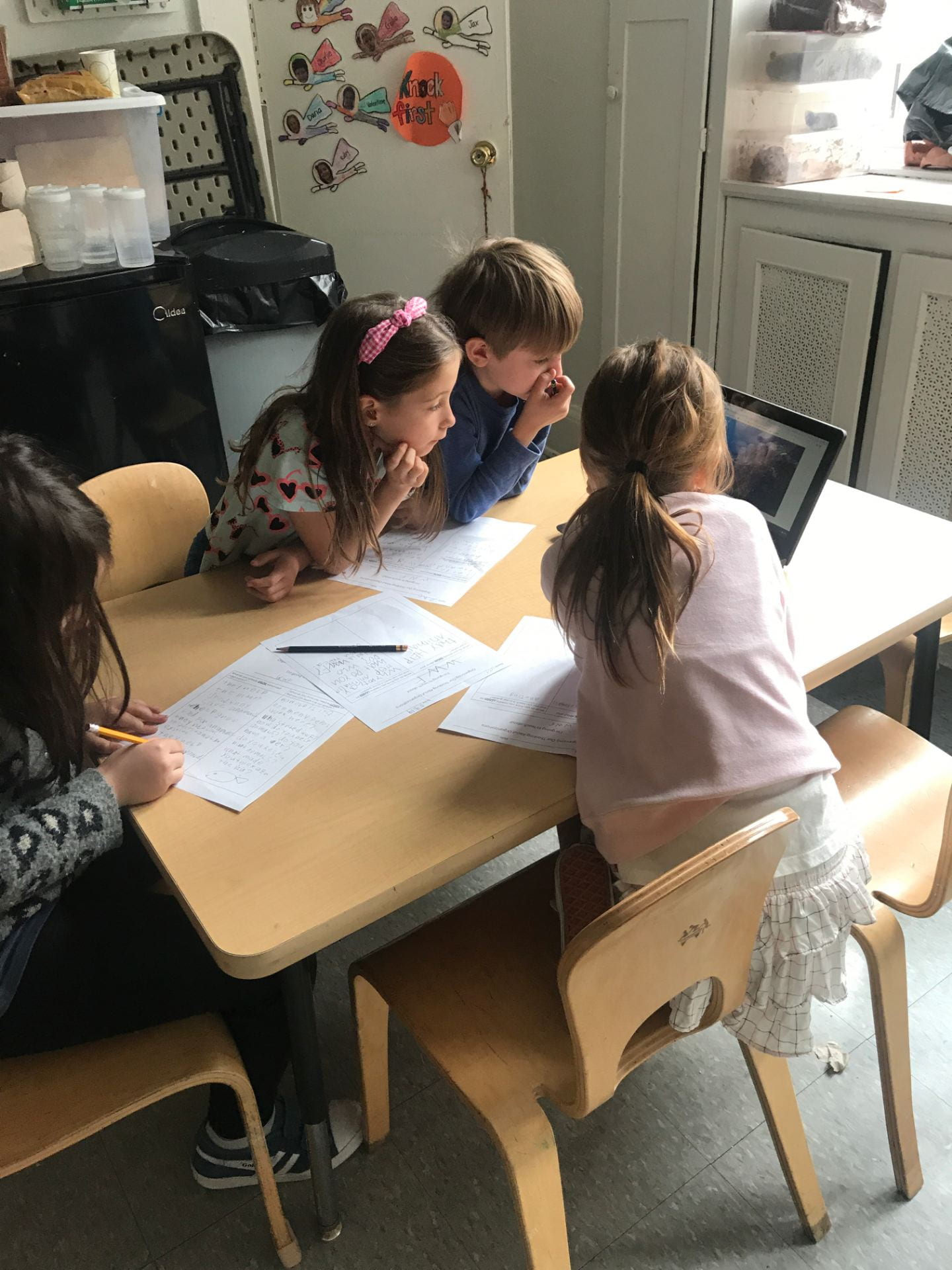

I started to think about my group of first graders and their difficulty making it through a 30-40 minute lesson, even when the lesson was divided into several different activities. Clearly their behavior was telling me that I was overloading their capacity levels, but simply shifting gears, a typical and usually useful strategy, was not working. If I pulled back and did less, would they learn more? And what would less look like? I started to think about resetting completely, starting from the beginning, then moving forward slowly to see how much they could take in. It was mid-year and my students should have been starting to read with some independence, but I found myself going back to alphabet skills. I was already instinctively incorporating more physical movement into our time together, but now I started purposefully building lessons that included breaks from sustained table time. The group’s favorite thing to do was “practice work”–time spent practicing the skills that they had learned, in a workbook. This is usually where I like to spend the least amount of time with my students, and yet they begged for it. I started to think about what it was about that work that appealed to them. Why did they gravitate to a workbook when they rejected or were simply unable to engage in so many more interesting and creative learning activities?

Clearly the structure and predictability made them feel more successful and secure in their learning. I have been thinking about what I can learn from that and how I can translate that into group work. When capacity for learning new information is low, and retrieval is disordered, the learning environment needs to be highly structured and new information has to be introduced in tandem with familiar information. This is not a new way to think about learning and teaching for me, and yet, I have started to think about it differently since examining the issue of capacity. I am thinking about the same things that I always think about but now with a new filter. The next logical questions for me are, “Is capacity for learning new information in a set amount of time diminishing? And if so, why? Is technology playing a role in this? Are we using language differently?” Are children entering first grade with the same amount of information as previous groups of children or is their foundation just a different foundation? I am not alone in having noticed that children’s vocabularies are diminishing and words that were once familiar, no longer are. “What is the connection between changes in language development and changes in learning?” These are the next questions that I will be thinking about as I move forward. When we left the NYSAIS conference we were asked to make suggestions for next year’s conference topic.I suggested examining the connection between technology, brain development and learning. Until we all understand more about this, it will be difficult for any of us to adapt our teaching.

This year gave me the time and opportunity to learn more about working memory, to experiment with different approaches in my classroom, to think about my own learning and teaching style in relation to that of my student’s learning and to delve into questions about how educational approaches may need to shift in order to meet the changing needs and learning styles of our students. It also opened up new avenues of thought that I will continue to pursue moving forward.