Essential Questions:

How do I get better at using literature to center conversations around racism and whiteness in middle school humanities?

The eighth grade humanities loosely spans the Civil War through the Civil Rights period, and includes a study of current civil and human rights issues through the social justice project. As such, issues of whiteness and structures of racism built into the foundation and systems of the United States is a major part of the conversations we have. I use literature to help surface and discuss race, racism, racial identity, race as a social construction, whiteness, and white privilege, and each year I try to reexamine my methods, identify my own implicit biases, and create more relevant, personal, unbiased and effective lessons. As incidents of racial violence against people of color at the hands of police and racial violence perpetrated by home-grown white supreamicist groups are increasingly alive on our social media feeds, and as racist dogma has been legitimized in a Trump Presidency, this work seems even more pressing and difficult.

Following are the four books, with a short description, that we read together as a part of conversations involving race:

Following are the four books, with a short description, that we read together as a part of conversations involving race:

- Warriors Don’t Cry by Melba Patillo Beals.

- Memoir of Beals who was a member of the Little Rock Nine who desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1958. This book helps us discuss systemic racism in law, racial segregation, integration v desegregation, being an upstander, among other topics.

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brandon Kiely

- Realistic fiction story about racism, police brutality, white privilege, and activism told through the eyes of two high school seniors — Rashad, who is Black, and Quinn, who is white. This book helps us talk about implicit bias, structural racism, individual racism, white privilege, and allyship.

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- Semi-autobiographical novel about Arnold Spirit Junior, a 14-year old Spokane boy who leaves the Spokane Reservation to attend an all-white high school off the reservation. This book helps us talk about Indigenous history, Indian Removal, Indian Boarding Schools, systems of white privilege.

- American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang

- A graphic novel about the young Jin Wang, second-generation Chinese American who embarks on a journey to accept all parts of himself after being stereotyped as a foreigner because he is Asian. This book helps us talk about Asian identity, being a hyphenated American, “whiteness as American.”

After attending the Institute Teaching for Social Justice and Diversity and doing a deeper dive into the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Anchor Standards, I have been affirmed in this work, but have discovered gaps, missing perspectives, personal biases, and new opportunities to de-bais my curriculum. For one thing, when lesson planning this year I have started to ask myself more questions: What critical perspectives or experiences are missing from this unit/lesson/book? Does this lesson/book engage with race/racism/whiteness from a deficit model? How can I monitor what my students are feeling, thinking, and learning as a result of our conversations? Are white students left feeling empowered to learn more or guilt/ashamed? Are students of color left feeling affirmed or stereotyped/unheard?

I have made many changes to the curriculum this year following the anti-bias work and summer institute. Below are a few ways that the curriculum has shifted this year. I have linked the changes with the Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Anchor Standards that helped the reframing.

Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standard #5

Students will develop language and historical and cultural knowledge that affirm and accurately describe their membership in multiple identity groups.

Rethinking Class Books

The biggest change this year in the humanities curriculum related to race and literature was to remove To Kill A Mockingbird from the line up. Even with it’s beautiful language and wonderful characters, the summer institute affirmed my growing concern that the book centers white experiences, learning, and personal growth at the expense of black character’s pain, second-class citizenship, and death. How affirming is it that Tom Robinson’s perspective is never shared? How come we don’t meet Helen Robinson in her own words? What does Calpurnia really think? The book presents the entire story through Scout’s perspective, which on one hand can be revealing and celebrated, but on the other hand is dismissive of characters whose lives are at stake.

Multiple Identities

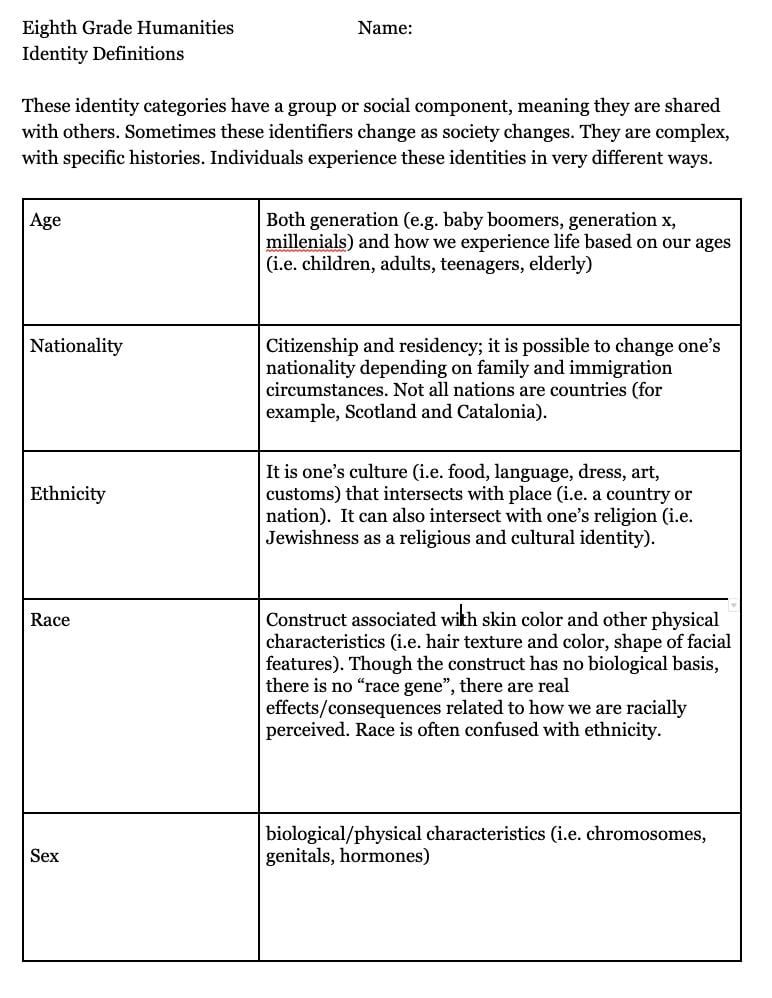

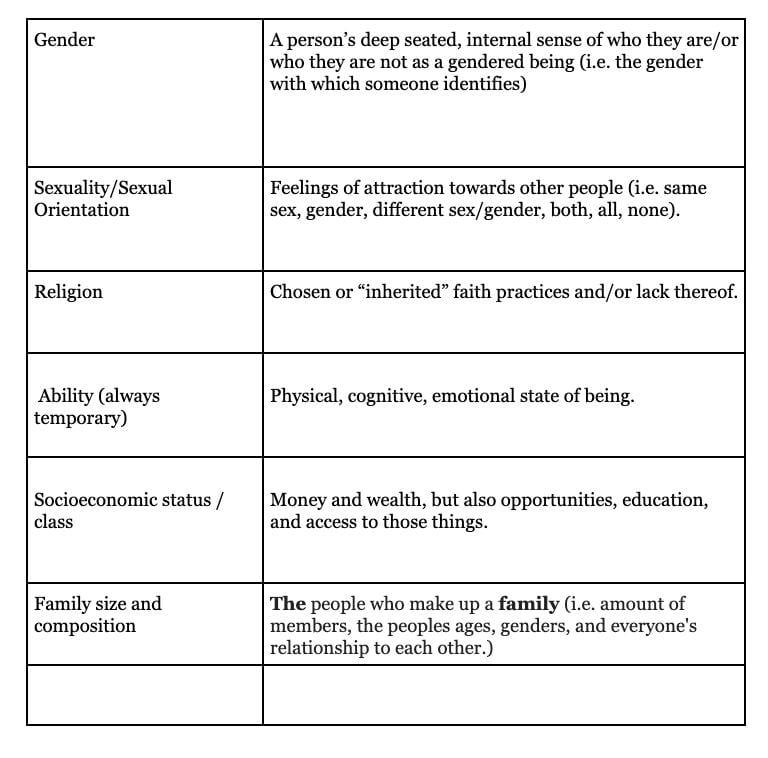

This year I wanted to ease into the conversations about race by starting with Standard#5, which prompts each student to start at a place together where they see that they are all part of multiple groups. We discussed eleven BIG identities, journaled about our own identities in each category, and then discussed which identities were visible and which were invisible to the outside world. Eighth graders had interesting conclusions about the universal experience of being human after this exercise:

“People are complex.”

“Many visible identities are misleading.”

“Identity is complex and changing.”

“Many of the most important parts of our identity are invisible.”

These discussions helped lead students, specifically my white students, into conversations about the relevance of race as a social construct and as a lived reality. While some of the most important aspects of identity are invisible, they recalled, aspects of some people’s identity, like skin color (i.e. race), supercede all others. White students reported to be shocked at how absurd and unjust it was that race prevented Melba, for example, from attending Little Rock High School.

Using our identity writing, we created a class constitution for the first time this year. Connected to our reading of sections of the U.S. Constitution and mimicking the preamble’s model, my hope with this was to be intentional about creating a classroom where we could be in community, have a shared understanding of our needs and commitments, and hopefully this would translate into better, more honest, race-related conversations later.

Multiracial-ness

The initial lessons about multiple identities, some visible and some not, some persecuted and some favored in society, naturally led us into more nuanced conversations about racial identity in Warriors Don’t Cry. While in the past, I’d never complicated the narrative that Melba and her family are African American. It became clear to students in conversations this year that not only was Melba’s mother proud of her Native background, but that she was able to pass for white in some circumstances and was the first Black woman to teach at her college in Little Rock. Broadening our discussions about the racial identities of people in our books was an important contribution to the discussions about race, racism, and whiteness.

This year I also decided to talk more specifically about how I come to my teaching with a lifetime of being asked “What are you?” I identify as biracial and have Japanese-American with Scottish/Irish ancestry. I am often seen as racially ambiguous/white passing. My immediate family members are all different races than me. My oldest son identifies as Black, with Afro/Indian-Guyanese, Japanese-American, and Irish/Scottish ancestry. My 3 and 5 year-olds are Puerto Rican and Japanese American with Scottich/Irish ancestry.

Teaching Tolerance Social Justice Standard #12:

Students will recognize unfairness on the individual level (e.g. biased speech) and injustice at the institutional level (e.g. discrimination).

Using the identities lessons as our background, I started discussing racism and the construction of whiteness in the United States in new ways. I started with the statement: “America is a work in progress.” Students journaled, thinking about why this statement was true.

“We say we’re equal, but we aren’t because there is still racism in society.”

“Our ideals were never fully true because the people who wrote them also owned people.”

“I don’t agree with this statement because we aren’t progressing. We have a lot of problems and they are getting worse.”

After students grappled with the concept that “American is a work in progress,” Nicole-Hannah Jones’ 1619 Project article provided a new and invaluable next step in our conversations.

Complicating Typical Narratives

When in the past our conversations have been largely two dimensional (i.e. integrated schools = good, segregated schools = bad), this year I dug deeper into this notion. First off, I interrogated the difference between “integration” and “desegregation.” According to Merriam-Webster dictionary, integration means “incorporation as equals into society or an organization of individuals of different groups (such as races).” I added information from Emory University’s Vanessa Siddle-Walker’s work about the destructive impact that “Brown v Board” had on Southern Black schools, many of which were amazing institutions at the heart of the community. We talked about how Black Principals, teachers, and other Black educational organizations were demolished post-Brown when white schools refused to hire Black educators. This left a dearth of African American educators in newly desegregated white schools. The impact of not truly creating racial “integration” has had consequences that are present today.

What are students learning?

As a part of the anti-bias approach, I wanted to gather some data directly from eighth graders about their impressions and learnings related to race. I asked four questions:

- What thoughts do you have about our conversations on race, racism, and whiteness in humanities class?

- How have these conversations impacted you personally, if at all?

- Is there anything you think is missing or needed?

- At what other times do you talk about race, racism and/or whiteness?

“I absolutely love talking about race; it’s full of opinions, experiences, and shock.”

“I am very used to talking about the disadvantages people of color have in society, but not really the advantages of white people.”

“I think we should look at more of the opposition.”

“Because I’m a white girl I feel like if we have conversations I will say something offensive and so I normally don’t speak about it.”

“When we have these conversations I feel a little off because I, for one, do not feel the pain of being discriminated against.”

“As a white person, the conversations didn’t impact me that much.”

There is a lot of work to do. Onward.

This is such impressive, important work. Thanks for sharing your process with us, Momii! This quote really stood out and describes why it’s so important to do this with and for our white students especially: “I am very used to talking about the disadvantages people of color have in society, but not really the advantages of white people.” Also, your sharing your own identity reminds me of the identity shares Karima, Jessica and Clair are doing in the fifth grade this year.

Momii, I think there is something profoundly important in your student’s bearing witness to the ways that you are interrogating the curriculum itself. I think it can’t help but change for the better all students’ relationship to what we traditionally see as the content of the curriculum. We sometimes take for granted the “fixedness” of the content (e.g., “Of course we’ll always teach To Kill a Mockingbird; it’s an essential text.”) In modeling this work for students, I imagine that you are finding new possibilities for yourself as a teacher and in doing so, creating new possibilities for your students. I’m excited to see how this unfolds.

Inspiring to read about the work you do and have brought to the eighth grade curriculum. You captured so many things so elegantly here and your work last summer spurred on so many deep and thoughtful changes. I didn’t know you’d gathered that data–so great. Love to hear even more! Your tireless work is paying off for all.