Essential Questions:

- If we want students to learn to do the work of scientists, not just learn about science, how can that be done without recreating within our classrooms the culture that currently exists in science outside of our school?

- If the past 500 years of science had been created by everyone, what values and beliefs would we hold about science? And if we want to do something about that now, what values and beliefs should we aspire to hold in our classroom?

- What routines, activities, and systems of feedback are necessary to create a culture of science that is built by and for everyone and that can be carried beyond a single classroom?

- How do we help students align their actions with their values in science class?

Values and Beliefs about Doing Science and Physics Class

In November, I tried this lesson (below) in my 10th grade physics classes. I’ve joined an “anti-bias task force” at my school made up of teachers from all divisions (lower, middle, and high school) who are looking at their curriculum and implementing lessons or other changes to work on removing bias and improving what and how we teach. I’ve decided to focus on the culture in my 10th grade physics classes.

If we want students to learn to do the work of scientists, not just learn about science, how can that be done without recreating within our classrooms the same science culture that currently exists outside of them?

One essential question guiding my work for this team

There are others looking at this same question, of course. Many focus closely on the disproportionate representation (by gender, race, etc) in physics. Some are programs like the disappointing STEP UP 4 WOMEN (which has rebranded as simply “STEP UP”) work from a deficit model. They are built on the assumption that the reason some groups are underrepresented in physics is that more girls—and/or more students of color of all genders, although STEP UP only focuses on girls and leaves race out of the discussion—simply need to be shown that physics exists and that they are allowed or able to do it. They view the problem as a lack of inspiration.

I find that a frustrating perspective. It’s also one that, despite lots of money and time being poured into it, so far hasn’t seemed to solve the actual problem. Here’s a tweet where I expressed that two years ago:

For more of my critique of STEP UP and their approach to solving this problem (having high school teachers recruit one more girl each year to study physics in college), here’s an entire thread from July of 2018 (where I unfortunately didn’t notice that I wrote STEM instead of STEP):

Okay, back to the purpose of this post and the lesson that I created in November.

Physics Class Identity Lesson

For the anti-bias task force, we were asked to create and lead an “identity lesson” in the fall. Since I am focusing on the culture in my classroom (and since the high school students have opportunities to think about, explore, and discuss personal/individual identity in many ways at my school outside of science classes), I decided to think about our identity as a class. I wanted to examine on what we believe and value—and what we should believe and value—about science and about learning.

This lesson was done in a single 65 minute class period with 10th graders. It took close to the full time, with up to 10 minutes left over in the different sections.

Part 1: The Past 500 Years of Science

Students saw a list of new, random, 4-person groups when they entered the room.

I handed out an excerpt of an article for them to read, with these instructions on the board:

Read the article individually.

Underline or highlight one most significant idea.

(You should also underline or highlight a backup idea.)

The article is an excerpt from Mylène DiPenta’s talk at AAPT in July of 2019. (Just go and read the entire thing right now. No seriously.) This excerpt talks about the past 500 years of science, how so many groups of people were excluded from the development of what we now think of as science, and how impossible it is to simply “invite” those groups back into something that certainly isn’t what they would have created if they had been involved since the beginning.

Part 2: Small Group Discussions

After reading the article individually, the students spent time first discussing the article using this discussion protocol that a colleague suggested.

(The students didn’t exactly stick to the rules of the protocol, which mostly ended up being okay. I also chose it that morning and pasted it into a document to hand out without reading it closely enough. As I listened to kids reading it out loud during class, I immediately heard the repeated “she/he” and “her/his” language and regretted not rewriting it myself. I also looked over and saw one student crossing all of those words out and writing in “they”, “their”, etc. I fixed it immediately after class on my own copy, but putting this note here in case someone else wants to use it so you know to think about that first, too.)

After those rounds of talking, they continued the discussion in small groups by considering about this prompt:

Even before you started taking physics, what messages have you learned through pop culture (or elsewhere) about what physics/science is, who does physics/science, and what it looks like?

It was really interesting to listen in on these conversations. Students didn’t immediately understand the question (and I would probably build in some more scaffolding to get them there next time I do this). At first they thought they had never really seen physics represented in pop culture. Once they got started, though, they came up with lots and lots of examples.

Part 3: Individual Writing Prompt

Next, students spent a few minutes answering an individual writing prompt (on their computers, in a Google Form).

1. How have the messages you’ve learned about physics through pop culture affected your expectations for this class?

2. How have the messages you’ve learned about physics through pop culture affected the way you approach or interact with our physics class?

I haven’t asked students about publicly sharing what they wrote, and many of these responses were very personal so I won’t paste any examples here right now, but there were a variety of responses. Some were light and funny. Some were really heavy and earnest and thoughtful. I will note that many of my white students, and especially the boys, raised their hands in confusion during this part because they weren’t sure what to write. They didn’t think any messages from pop culture had affected their expectations or their approach. I told them to write whatever was true—so to write about that if that was true, of course.

Part 4: Beliefs and Values Card Sort

Next, I gave each group an envelope full of cards with beliefs and values written on them. They came from a pair of lists that I generated (with a LOT of help from other teachers—see below) of beliefs and values that I hold in my classroom and beliefs and values that might be held in a conventional (or traditional/typical) physics classroom.

Here are the cards. They are separated into beliefs and values (not by the original lists), and I printed them on different colors. The beliefs versus values was really a grammatical distinction that I got hung up on and that I would want to revise and simplify a little with more time. (But it also didn’t cause any confusion with students.)

Students were first presented with this instruction:

At first, a lot of groups thought it was easy and obvious. As they worked, and with some encouragement from me, they started to realize that not everyone agreed with every card.

I told them there could be a middle pile. Most groups started putting cards in the middle, but most groups moved almost all of the cards out of the middle by the end as they discussed them more.

One group, told me that they thought the things that were about our class were written to be really positive while the things about traditional classes were really negative. So we talked about that a little (and it also led to, again, them realizing that they didn’t actually all agree on which were positive and which were negative).

I was struck by how attached the class was to the importance of individual achievement, even amongst their (on average) mostly radical views about what was important. It’s completely impossible to live without being affected by the culture surrounding you.

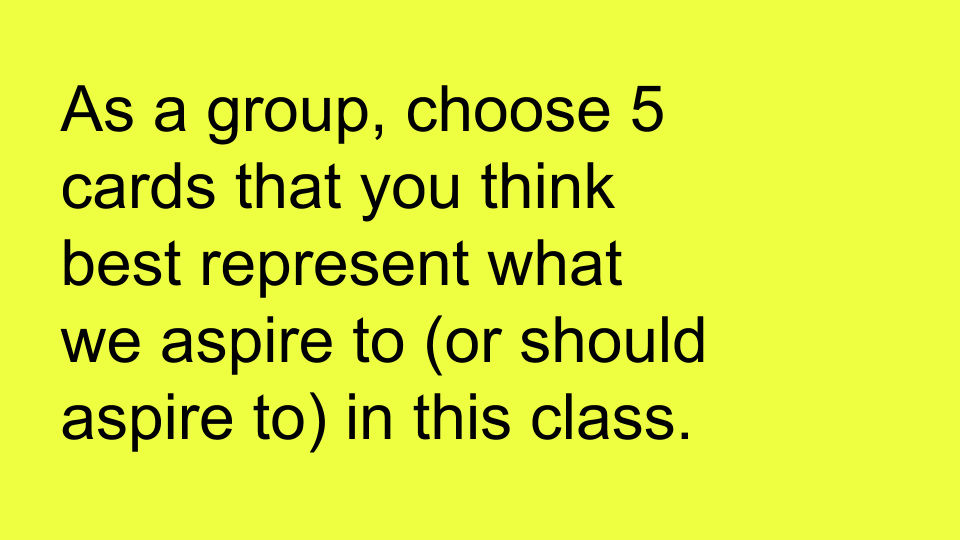

Once they had sorted the cards, I gave them this instruction:

Once the groups had chosen their cards, I paperclipped their choices to the outside of each envelope (with the rest of the cards put back inside). That night, I put their responses into a spreadsheet and generated a quick bar chart showing their choices for what we should aspire to in our class.

Part 5: Beliefs and Values into Action

To close the activity, I wanted to show students how choices that I’ve made in how our class works/runs relate to the beliefs and values that I hold about science, about them as students, and about how people learn.

The end of my slides (slides 8 through 13 below) have a small selection of the choices that I’ve made about how our class works and the values that those choices line up with.

This part of the lesson felt necessary to make sure that we weren’t just talking about philosophy and that we also talked about how to make our actions match our values. At the same time, this part felt like it wasn’t quite right yet. It felt self-congratulatory, and that wasn’t how I really wanted this lesson to end. Another place with room for growth for next time.

Next Steps

This is great and all, but if we leave it here, then it isn’t going to make much of a difference. So here is how I have already started following up on this one lesson.

Classroom Poster

I took their responses to the card sort (their choices for the beliefs and values we should aspire to hold) and created a (really boring) poster, which I printed at the FedEx Store (where you can make relatively cheap large format print outs in black & white) and posted on the wall in my classroom.

End of Trimester Survey

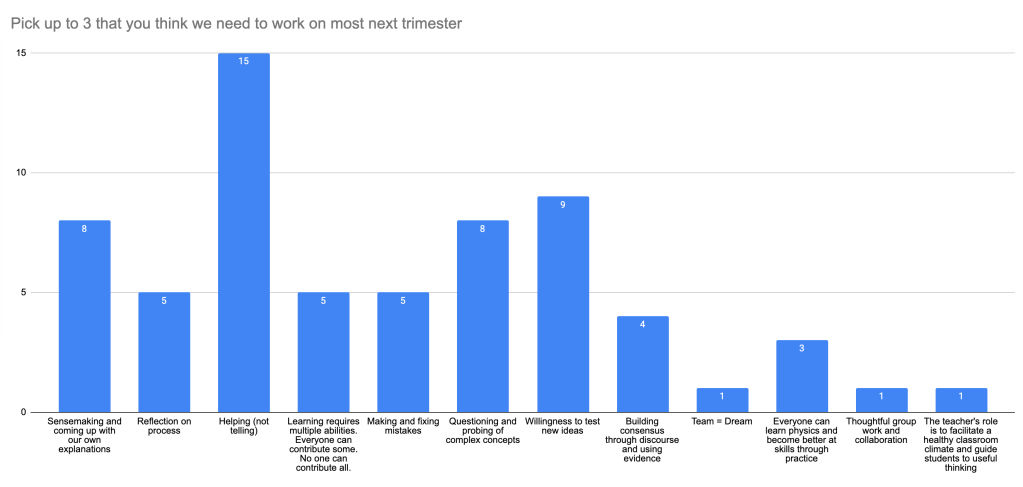

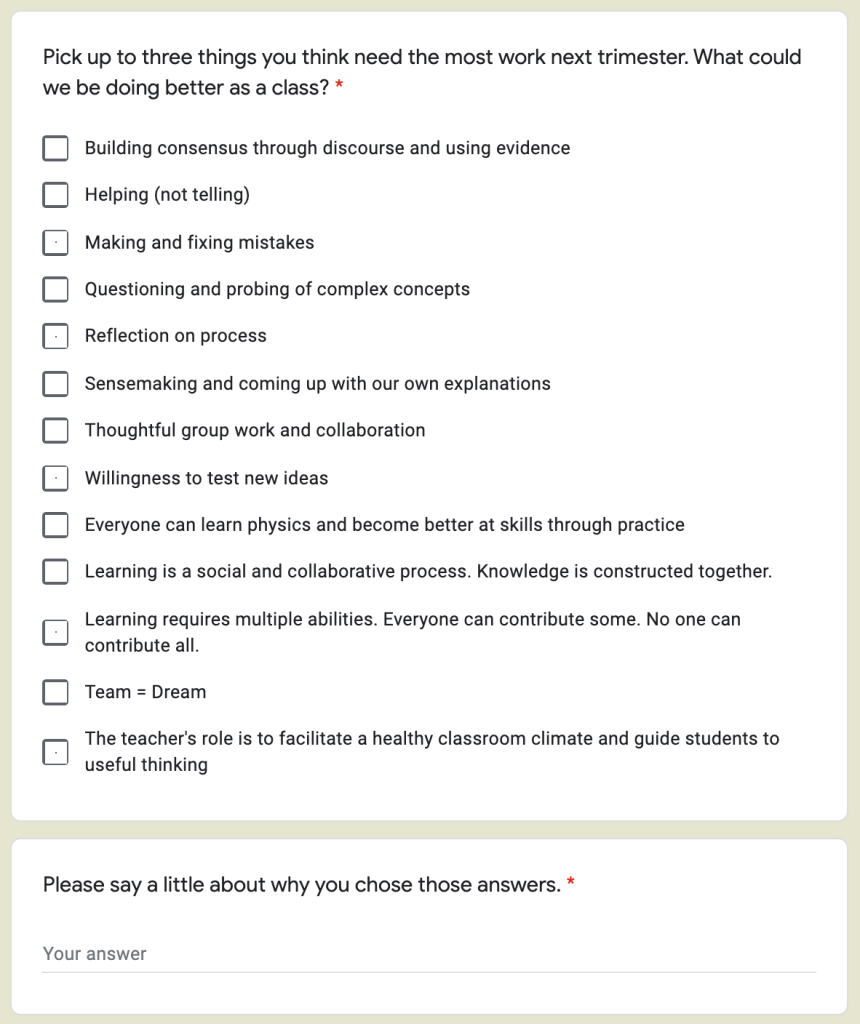

At the end of the first trimester (in December), I asked students to reflect on their list of beliefs and values that we want our class to hold by giving them a pair of questions:

I got a lot of really great and honest reflections from both sections of my class. Here are bar charts of their answers:

Next, I want to share these results (not only the bar charts, but summaries of their written responses) with them in some way so that we can continue to reflect on our work and keep improving together.

Sharing this post!

I am writing this post to share this messy first-draft work more broadly. I would love to hear any and all stories of anyone else trying this lesson (or a better version of it!) in their own classes. Please, please share!

I am looking forward to feedback, insights, and more as I figure out the next steps and iterations after this work (for this year and beyond).

Acknowledgements

So very many people helped me put this lesson together and deserve a lot of the credit for the content and results.

Mylène DiPenta, who gave an incredible talk (that I’m still processing) and allowed me to use part of it in my class.

Michael Lerner, Marta Stoeckel, Danny Doucette, Tiffany Taylor, and Brian Frank, the Twitter rescue team who helped construct the list that became the card sort, came up with discussion questions, and listened to me panic as I pulled everything together just in time for class.

My incredible colleagues at my school who listened to my ideas and gave me feedback and suggestions: Preethi Thomas-McKnight (who realized “this is a card sort”), Manjula Nair (who came through with the discussion protocol and encouragement the morning of the lesson after I emailed her the night before), Kara Luce (who you can see in some of the photos because she gave up a prep period to observe and support), Dr. Chap (who started this group in the first place), and Allison Isbell (who pushed me to actually just do it instead of waiting for it to be perfect, which it never will be).

Kelly, I’m continually struck by how deeply the habit of modeling thinking is grounded in your work with learners and in your own reflective process. Sharing the “messy first-draft” seems so crucial to this work and to our growth as a community of practitioners. There is also a deep respect here for the needs and insights articulated by your students, which I imagine are powerful orienting points for thinking about next steps. Many thanks for engaging in this work.