By Lucas Ritchie-Shatz

-SPOILER WARNING FOR IT: CHAPTER 2 AND IT-

Nobody weeps for the dead gay couple at the beginning of It: Chapter Two. Two gay men who express open affection for each other, so rare in non “LGBT” cinema, are brutalized by a homophobic group of kids. They are beaten and bloodied, and we see it all happen, flinchingly close. We see one of the couple struggle to breath- he’s asthmatic and has lost his inhaler. His body falls off a bridge and his partner runs after him, only to see the clown, Pennywise, about to eat him. The couple dies, and the opening credits roll. The real horror has not even begun.

Stephen King based this scene off of the real 1984 murder of a gay man, Charlie Howard, from King’s hometown of Bangor, where It is based on. In this way, Howard becomes just another one of Pennywise’s victims, a harbinger of what’s to come; he is as real as Georgie, one of Pennywise’s victims— perhaps even less, because after this scene neither him or his partner are mentioned again.

It, fundamentally, is about the trauma we face in childhood and how we possibly begin to heal. This is portrayed through the metaphor of a shadowy murderous clown, Pennywise, the physical manifestation of fears we’d rather keep behind locked doors. He eats children in the split-second their parents are turned away, he tells us that we are the freaks we fear to be, and he isolates us from the people who could really save us. But his most insidious deceit is making you constantly check over your shoulder. The people you love could be gone at any moment.

The strength of the main characters in It (2017), ‘the Losers Club’, is their defiance to being defined by the oppressive forces that threaten them. Each of the kids is surviving their own traumas, be it bullying at school or abusive parents (or both), yet in their words, it’s summer. They just want to be kids. Their love for each other, their fumbles towards adulthood, their vulnerability, is,what makes them strong against a villain like Pennywise. In the climax of It (2017), the Losers Club enter Pennywise’s lair together, and together, they get rid of the clown.

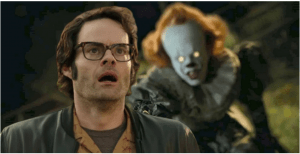

In It: Chapter 2, the Losers Club come back. 27 years later and now middle aged, they each have their own experiences revisiting the traumas they have tried to forget. In one particular scene, Richie Tozier, played by Bill Hader, revisits an arcade he used to frequent. In a flashback sequence, he is shown playing Street Fighter passionately with another kid, before shyly glancing at the ground and asking him if he wants to play another round. But his brief moment is crushed by the town bullies, whose appearance causes the other boy to tell Richie that he’s “not his boyfriend”. One of the bullies screams, “Get out of here, f*ggot!”, and Richie flees.

Later in the scene, Richie goes to the park, where he is handed a flyer by the dead gay man from the beginning of the movie. “In Loving Memory of Richard Tozier,” it says. He is taunted by Pennywise— “Why don’t we play a game, Richie?” Pennywise asks. “Truth or Dare? But you wouldn’t want anyone to pick truth, now would you? You wouldn’t want anyone to know what you’re hiding.”

There is something so painful about the character of Richie Tozier. He’s the comic relief of the Losers Club, and Bill Hader plays him with a startling amount of emotional weight. His story in the It remakes is an undeniably, if only subtextually, a queer one, and it is hard not to read his story in the context of my own. Being a queer trans man, I don’t relate to Richie’s situation in exact terms. But there are the individual experiences of being closeted I recognize- the counting of breaths between sentences, wishing for any way in. Trying not to slip up at performances you didn’t agree to give. Desperately trying to not break the rules you didn’t know were there. Thinking: when do I get to stop coming out? We escape these places we grew up in, we escape them to try and form ourselves anew. Yet we can never truly run away, never truly escape those pasts, and Richie’s character encapsulates that crisis of slipping back into a person you thought you would never have to be again.

Of course, it is not just Richie’s circumstances alone that make him a tragic character; we all have to go home sometime. No, it is his relationship to another member of the Losers Club, Eddie. In It (2017), Richie and Eddie are two of the most vibrant characters, and their moments together are some of the funniest in the movie. Eddie is the one, who, in the beginning of Chapter Two, has settled into his predetermined life. He has a wife resembling his mother and a nice, boring job. Yet as soon as he and Richie see each other again, they slip back into the same banter as when they were kids. It’s sweet, and in the context of Richie’s story, all the more painful. Which is why, of course, Eddie has to die at the end.

Eddie’s death is one of the most genuinely emotional moments in the movie. Bill Hader’s performance as Richie, holding Eddie’s body as his friends try to pull him away, screaming, ‘he’s not really gone!’ is powerful. For a horror movie about a clown, it managed to make me cry, just a little. And of course there is the scene where the surviving Losers swim in the lake of their youth, water as cleansing and rebirth, rejoicing in their victory, the two characters with an underlying love story, Beverly and Ben, consummating their love. Yet, Richie is off to the side. His friends recognize his pain and embrace him, grieving together. But something in Richie’s look conveys that although he loves them, they don’t really get it.

Eddie is a tragic character as well, besides just his death at the end of the movie. He has stayed much the same since those 27 years have passed- he still has his inhaler, still has his hypochondriac and neurotic tendencies. In a queer reading of this story, it’s hard not to see Eddie’s anxiety over sickness and disease (particularly in the first movie, AIDS) as a manifestation of a larger fear: sickness in himself, of being in some way unclean. It recalls comments made by people like Jesse Helms during the height of the AIDs crisis—“There is no known case of AIDs in this country that did not have its origin in sodomy.” AIDs is God’s punishment for homosexuality. To be gay is to be dirty, unclean, impure.

During one of the last scenes in It: Chapter Two, Richie and Eddie, reunited once again in Pennywise’s lair, are faced with three doors. They read, “NOT SCARY AT ALL,”, “SCARY,”, and “VERY SCARY”. The scene recalls a similar gag in the first movie, Richie recognizing it and reaching for the “VERY SCARY,” door. He slowly opens the door, revealing an empty closet. He pulls the light switch, and a boy’s legs come dancing out at them. He shuts the door.

After it’s all over, the members of the Losers Club get a letter from their deceased friend Stanley. As it’s read and every character is shown slowly returning to their real lives, Richie is shown carving initials into “the kissing bridge” from the first movie, a place where couples would come to leave their names. He recarves the initials, “R+E”, where they have grown faded over the years. In the end, this is how It: Chapter Two, sees its’ characters queerness: as means of evoking fear or tragedy. In the end, Richie and Eddie open the door and see a specter of their fears, a warning: this is what happens to gay little boys. In the end, the gay characters die or are left to suffer silently.

The biggest failing of It: Chapter Two, its treatment of gay characters, cannot be pinned wholly on either the book or the movie. Stephen King wrote a book using a hate crime as a plot device, and Andy Muchietti chose to frame Richie and Eddie’s tragic relationship as a gay one. In reality, what I hoped for, what I wanted for Richie and Eddie was never going to come from an adaptation of a 1986 horror novel about a clown. But what has captivated me about their story, what has captivated many others, is how we see ourselves in the relationship between these two boys and their fear growing up and of things that they don’t understand. After all, that’s what initially captured so many people about It and much of Stephen King’s work, his ability to render childhoods we recognize and creatures we don’t.

This meta-acknowledgment of gay relationships seems to be becoming the norm for television and movie adaptations that want the recognition of the LGBT community for gay representation without sacrificing heterosexual audiences. While It: Chapter Two has to be the most explicit example of this in recent history, others that come to mind are the recent miniseries adaptation of Good Omens and The Goldfinch. This seems to be the new evolution of the tongue-in-cheek queerbaiting that proliferated television screens back in 2013 with shows like Sherlock, Hannibal, and House, MD. While these adaptations frequently involve many of the same tropes a lack of romantic prospects for either character, gay coding such as the “sissy stereotype”, each character being portrayed as the other’s ‘one true friend’—actors, writers, and directors are now willing to acknowledge the gay underpinnings of these relationships in interviews or on social media, instead of just fan theories. Indeed, as previously mentioned, It: Chapter Two points very directly to a gay reading of Richie’s character. Bill Hader, has spoken to the character’s sexuality, as has director Andy Muchietti and Stephen King. The one element they are all missing is any explicit consummation of a gay relationship.

It: Chapter Two and its failing of its gay characters, then, just feels like a microcosm of the larger struggle for representation that Hollywood currently faces. LGBT audiences are a market that studios are increasingly trying to tap into, if the 66 million dollar success of Love, Simon is any sign. But studios are simply not willing to sacrifice straight audiences, especially if it means a genre film gets labeled as an LGBT one. So in the end, this is what Richie gets—a dead best friend and a clown that calls him slurs.

Photo Credit:

https://screenrant.com/it-chapter-2-movie-opening-violence-bad/